/

The GFC rewired how allocators evaluate emerging managers. Learn why stress testing, liquidity planning, and survivability now matter more than Sharpe ratios.

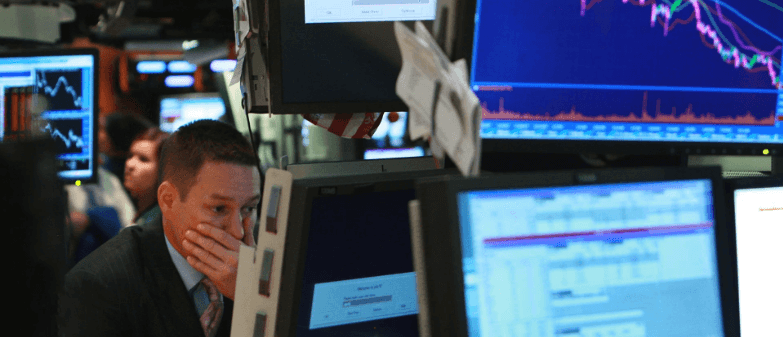

Between October 2007 and March 2009, the S&P 500 fell 57 percent from peak to bottom. If you're raising capital for an alternative trading strategy today, you're still living in the afterglow of that number. Before 2008, a good story and track record opened doors. After 2008, allocators rewired their questions entirely. They started asking about counterparty risk, funding resilience, liquidity waterfalls, and stress paths with an intensity that simply didn't exist before. That intensity hasn't faded, it's just become invisible. It's the water allocators swim in now. Your fundraising strategy lives in that context, not in a vacuum.

The Shift: Before and After 2008

The distinction is sharper than you might think.

Before 2008: Allocators evaluated emerging managers primarily on performance and strategy. They looked for edge, Sharpe ratios, experienced teams. If the numbers were good and the story was compelling, capital followed. Due diligence existed, but it was often more about confirming competence than stress-testing survival.

After 2008: Allocators still care about performance. But performance became table stakes, not the decision. The real evaluation shifted to a completely different question: If the world breaks again, will this manager and their fund structure survive, and will they protect my capital during the chaos? This wasn't regulatory change alone. It was psychological. Allocators who watched portfolios fall 40–60% while facing redemption requests they couldn't meet learned something visceral: strategies that work in normal markets can catastrophically fail in stress markets. The managers who survived weren't always the ones with the best five-year track records. They were the ones who'd thought deeply about what could break, and had built defenses against it.

Chapter Zero: The Invisible Decision Framework

Here's what most emerging managers miss: every capital raise conversation today has an invisible Chapter Zero.

It's not your latest performance update. It's not your strategy explanation. It's not your track record chart.

Chapter Zero is the allocator's own experience of 2008.

They remember seeing equity indices almost cut in half. They remember watching credit markets freeze, not gradually, but suddenly, with spreads gapping and counterparty names disappearing from the prime brokerage landscape. They remember the feeling of being responsible for capital in an environment where price, liquidity, and solvency all felt uncertain at the same time.

That memory isn't historical. It's actively shaping their decision-making framework.

You walk into the meeting thinking the conversation is about your strategy. The allocator is actually evaluating whether you understand what it feels like to manage capital through an existential crisis. Whether you've built safeguards against your own potential failure. Whether you're someone they can trust with serious capital when normal market assumptions break down.

If you haven't prepared for that evaluation, if your deck and your risk framework don't directly address 2008-style scenarios, you've already lost the conversation, even if your strategy is sound.

Three Things 2008 Changed (That Still Matter Today)

The GFC fundamentally restructured what "fundable" means in alternative trading. Three shifts in particular still define how allocators evaluate emerging managers:

1. Liquidity and Leverage Questions Became Non-Negotiable

Before 2008, allocators might ask about liquidity and leverage casually. After 2008, these became existential questions.

Because they watched managers who seemed safe get caught in liquidity traps. A manager with strong fundamentals and decent risk controls could still blow up if they couldn't access liquidity when they needed it. Or if their leverage assumptions, "I can always access 3:1 leverage on this collateral", got called in a crisis.

Today, allocators ask about liquidity with clinical precision: What happens if your broker reduces your leverage by 50% overnight? Where does your strategy break if liquidity dries up? What's your relationship with multiple execution venues? How do you stress-test your positions against liquidity scenarios, not just price volatility, but actual illiquidity?

If your answer to any of these is vague, or if you're still assuming normal market liquidity in stress scenarios, you'll hear the same polite "we'll circle back" that kills most emerging manager fundraises.

2. Stress Testing and Scenario Analysis Became Core Due Diligence

Before 2008, stress testing existed but was often theoretical. Risk departments ran models. But most allocators didn't deeply interrogate what would happen if historical correlations broke and volatility spiked.

After 2008, stress testing became the language allocators use to evaluate survivability.

You see it in Due Diligence Questionnaires (DDQs). Question 47 isn't "What's your Sharpe ratio?" It's "Walk us through how your portfolio would have performed under a 2008-style drawdown."

You hear it in conversations. The discussion moves quickly from "What do you trade?" to "How does this behave if correlations go to one? What if your largest position gaps against you 20%? What if funding costs double overnight?"

Allocators want to see that you've actually run these scenarios. Not backtested them optimistically. Actually thought through what breaks, when, and how you'd respond.

3. A Permanent Bias Toward Managers Who Think About Risk Before the Crisis, Not After

This is the subtlest shift, and the one that most separates fundable managers from unfundable ones.

Allocators learned in 2008 that managers who survived tended to have one thing in common: they'd already thought about crisis scenarios before they happened. They had rules. They had position limits. They had drawdown stops. They had counterparty oversight.

The managers who got blown up often made their crisis preparations after things started breaking. They realized too late that their risk controls didn't work in stressed markets. They tried to sell and found no one would buy. They tried to reduce leverage and found their brokers had already done it for them.

Allocators now have a permanent bias toward managers who can demonstrate they've thought deeply about risk in advance. Not as an afterthought. Not as a compliance checkbox. As the foundation of how they operate.

Where You See This Today: The Invisible Questions

If you pay attention, you can see the 2008 framework embedded everywhere in how capital is raised today.

It's in how DDQs are written. The questions aren't just about returns. They're about what breaks, where it breaks, and what you'll do when it does.

It's in how conversations move. Allocators don't want to hear your edge explained. They want to understand your survival plan. They want to move from "what do you trade" to "how does this behave if everything breaks."

It's in how often they ask about margin calls and collateral, even when you're not a highly levered strategy. They're not asking because they think you're reckless. They're asking because they learned in 2008 that being caught off-guard by funding disruption is a manager-killer.

It's in how skeptical they are of strategies that "worked through 2008" because the strategy didn't exist then. They want to see stress tests that show how you would have performed. Not because 2008 will repeat exactly. But because it's the historical worst-case they have in their memory.

The Real Job: Building for a World Where 2008 Happens Again

Here's the uncomfortable reframing that most emerging managers avoid: Your job in a capital raise isn't to convince allocators that 2008 won't happen again. Your job is to convince them that if something like 2008 happens again, in a different form, with different triggers, you won't force them to relive the worst parts of that experience with you.

This is why the allocator doesn't care primarily about your Sharpe ratio. They care about whether you've built safeguards against catastrophic failure. That requires more than a slide labeled "Risk Management." It requires being able to show, in concrete terms, that you understand the real risks and have built defenses.

What Allocators Actually Want to See

1. How your strategy would have behaved under a 2008-style drawdown in your asset class, even if it didn't operate then.

Not an optimistic backtest. An honest analysis. "Here's what happens to our FX strategy if correlations spike and volatility triples. Here's what happens to our systematic strategy if historical patterns break. Here's what happens to our discretionary book if three major execution venues become illiquid."

Show them you've actually done this work.

2. Where your liquidity assumptions break, and what your plan is when they do.

Don't assume you can always trade. Don't assume leverage will always be available. Tell them: "At $5M AUM, our largest position is 8% of average daily volume. At $50M AUM, it's 40%. Here's how we adjust execution and position sizing as we scale. Here's what happens if one of our brokers pulls leverage. Here's our backup liquidity provider."

Specificity signals you've thought this through.

3. How you think about funding stress, margin expansion, and counterparty risk, not just price volatility.

Price volatility is what most emerging managers focus on. Allocators focus on operational risk. "What's your prime brokerage relationship? Do you have backup brokers? How often do you reconcile positions? What happens if your custodian has a problem? How do you think about counterparty exposure in your trading?"

Allocators learned in 2008 that operational survival matters more than strategy survival.

The Uncomfortable Reality: This Is Now the Bar

For many emerging managers, this level of rigor feels like overkill. You have a good strategy. You've proven it. Why do they need stress tests and liquidity waterfall analyses and counterparty frameworks?

Because for allocators who watched portfolios fall by double digits and faced redemption pressure at the same time, this isn't overkill. This is table stakes.

The GFC did more than change regulations or bank behavior. It changed the invisible benchmark of what "fundable" looks like in alternative trading. It's higher. It's more rigorous. And it's focused less on strategy brilliance and more on operational survivability.

That's the world you're fundraising in now.

When you prepare for your next allocator meeting, it's worth asking yourself a simple question: If the person across the table still carries 2008 in their decision-making, have I given them a reason to believe that my strategy is built for a world where that kind of crisis happens again? Or am I quietly assuming that a good Sharpe ratio will make them forget?

Because they won't forget. And they're not going to fund someone who hasn't thought through what happens when normal market conditions break. 2008 wasn't the worst markets can do. It was just the worst they've personally experienced. And that experience is the invisible benchmark every allocator uses when they evaluate whether to give you capital.

Build for that world. Show that you understand it. Prove that you've prepared for it. That's how you fund a strategy in the post-2008 era.

Frequently Asked Questions

Articles you might like